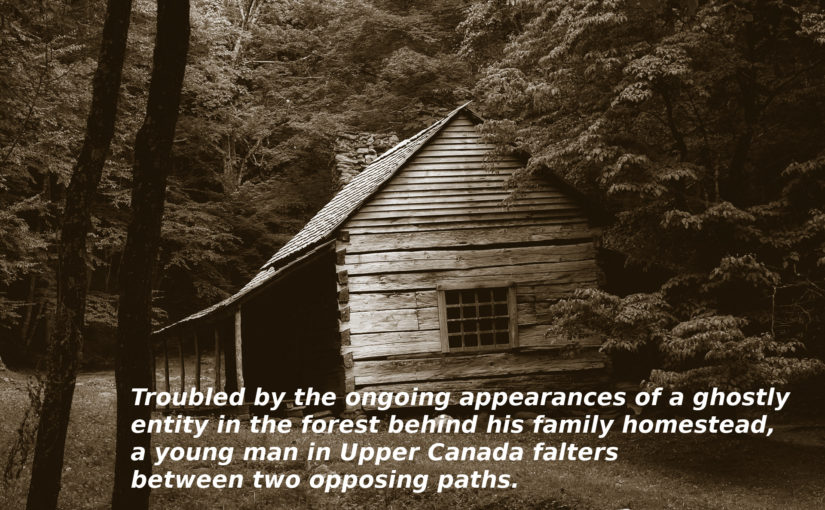

I twisted around to see what had startled her, and there it was. A white entity floating through the distant trees at the back of the field, then vanishing as it moved deeper within. Goosebumps prickled my skin.

“Mother’s angel,” she whispered. “Did you see it?”

Indeed I had, but was not about to admit it.

“Don’t be silly,” I said with a scowl, heading toward the cabin with quick, long-legged strides. “Your imagination is getting the best of you.”

She hurried to catch up, lantern light waving back and forth across the path as she ran. “Oh, but surely you saw it,” she cried, “you looked right where it was, I know you did.”

“Stop talking nonsense.”

Hurt filled her eyes as I glanced back over my shoulder, and I couldn’t bear it. Scowl deepening, I went up the stairs to the front porch, opened the door and tramped inside without bothering to let her go first.

She never mentioned the sighting to me again, though I did hear her discussing it softly with Ma while they cleaned up from supper together that night. I sat in front of the fieldstone fireplace in a brooding silence, stoking it from time to time—my cheeks still burning with anger when I finally went to bed. Awaking early the next morning to relight the fire, I knew the anger had been shame. But I could not bring myself to apologize.

When I was sixteen my father said it was high time I started making the journey to the gristmill with him each harvest, as he could certainly use the extra muscle. And though he didn’t say it, I hoped he was also seeking my companionship. My excitement with this announcement was enormous, but I kept my demeanour steady, lest I resemble a giddy little boy on some happy Christmas Eve. For this wasn’t merely a journey to the mill for me. I felt instinctively that it was to be the inception of manhood.

We didn’t share much conversation on that first journey but sat quietly side by side on the wagon bench; taking turns driving the horses, and keeping an eye out for ruffed grouse in the undergrowth. Father carried his fowling piece over his shoulder, as he always did while travelling, and stopped the wagon on occasion to go after a bird; of which he eventually bagged two. The weather was fair, and we arrived in the Town of York by about noon day.

While churches and schoolhouses were yet scarce, there seemed to be a tavern every few miles along the main road; though this ratio would gradually change. We stopped in at one such tavern for refreshment before continuing on to the nearby mill. I’d never been in a taproom before, but I did not find it overstimulating. It wasn’t until we returned in the evening, when the place was packed with pipe smoke and noisy patrons that I grew dizzy and intoxicated by it all: even though I’d only had green tea to drink.

Though most of his commentary up until this point in the journey had been of a practical nature—Pa now began to talk in a looser, less purposeful manner on subjects that were entirely new to me. He had acquaintances here, I soon discovered, men he caroused with whenever they happened to be in the same tavern at the same time. There were not many women about, however, just the occasional one who entered through a side door to place an order before leaving again—usually accompanied by a husband, though not always.

I at once noticed the change in demeanor of the men whenever a lady did enter the room alone: not to a more formal, respectful manner, as I might have expected, but rather to a leering one. And the remarks made whenever such a lady left seemed of a lascivious nature. Even still, having no personal experience, I felt that I was likely missing much of the intended meaning. I was too young. Nevertheless, my cheeks burned hotly the entire evening and this had the effect of fueling the men on all the more. It was almost as if they enjoyed my discomfort.

And though pleased that they counted me mature enough to participate in their merrymaking, I’d be lying if I said these ribald jokes weren’t a continual shock to me. For though my father had sometimes disparaged women in his conversation with me, it was only ever about their inferior wits and emotional nature. Many years later I came to reflect on how this mentality was rooted in the intimidation he felt from being married to an educated woman—an insecurity he found difficult to reconcile with social mores—and the effects of growing up without a mother’s influence. If he could have swallowed his pride, he might have enjoyed a far more satisfying relationship with his wife, and she in turn, with him.

Throughout the following planting and harvesting seasons, I was to visit this same tavern with my father several more times; as often as he could possibly find a legitimate reason to travel so far from home. Our crops were profitable and he sometimes arranged to trade with Indian hunters who were pleased to exchange fish or venison for flour and oats. On these sundry excursions Pa drank whiskey to his heart’s content; something he was not able to do back at the family cabin where homemade beer was all we had. Mother did not allow drinking to excess and he’d never challenged her on that, though I suppose this was likely only because his comrades weren’t there to make the drinking worthwhile.

There were times—too many times—when I had to help him stumble from the taproom to the stable where our horses awaited so he could then sit half-snoozing all the way home, startling awake with every rut in the road. And if we planned to stay overnight and had taken a room at the inn, it was usually necessary to help him to bed too; he hanging over my shoulder with nearly all his weight. This was of little exertion to me, however, since I’d reached the same height as him and was just as strong, if not more so. Usually he was sober by the time we arrived home but I could always tell by the stern look on my mother’s face that she knew what he’d been doing. No doubt she could smell it on his breath as well.

I don’t know which I found more unsettling in those days, her resentment toward father or the felt sadness when she searched my face: her little boy nearly a man . . . nearly a man like his father.

As that year passed and the next, I learned the lingo of these men very well and understood much of the licentious commentary, though my experience with the female sex remained vicarious. I’d also ascertained that two wanton women who stood in front of the tavern at night were prostitutes. Though my father never did anything beyond eyeing them with interest, some of his comrades went away with them to the inn, only to return an hour later to share their enviable experiences with our itching ears. And so it was that I began to see women as two halves of a whole, like a cloven hoof.

On the one side there was Ma and my sisters, my auntie and cousins—chaste, respectable, demure—and on the other, the harlots—alluring, entertaining, dissolute. A woman who could be a good wife and physically desirable at the same time was inconceivable to these men. Women were for one use or the other, even, I’d found, in literature.

As women became two halves of a whole, I found myself splitting in two as well. The man I was with my relatives, and the man I was becoming with my father at the tavern. The man I was reading aloud to the family and the man I was when I went to sleep at night with my private dreams. Two irreconcilable modes of being.

Eventually, insidiously, I found my anticipation for each trip decreasing while my hunger for greater thrills increased. This discontented, restless state weighed on me continually, becoming an albatross around my neck. And though Pa seemingly enjoyed hearing about his friends’ conquests and did not discourage it, he was quick to scold me whenever I showed any intrigue myself. I sensed he derived pleasure from dipping himself in it while avoiding full immersion, and wanted me to show the same restraint. Deep down I believe his love for mother and his duty to his children held him back; a devotion he kept hidden beneath a melancholy demeanor and the odd snide remark.

In this frustrating position, where indulgence through imagination was no longer satisfying—despite having observed the long-term, pernicious effects such indulgence could take on a man—I was surprised to find myself yearning for those younger years when my greatest delight was the chance to sit at Ma’s feet after a busy day while she rocked beside the fireplace reading stories to me and my siblings. Or taking the one hour wagon ride to my aunt and uncle’s homestead for a much coveted visit with cousins . . . traveling as a family to the general store for supplies and receiving a little treat . . . stringing up chains of popcorn and evergreen garland around the cabin at Christmastime . . . singing hymns together on the Sabbath. The days when my dreams and anticipations were wholesome and pure; when those activities hadn’t yet become dull and puerile.

I also missed Ma tucking the quilt up to my chin each night, saying a prayer, and kissing my temple. Our cabin, built by my grandfather, was larger than some of our neighbors’ homes, and consisted of three rooms: two cramped ones for the beds, and a bigger main room where we did all of our cooking and reading. At first my sister and I shared a jack bed, but as each baby grew older and left the cradle, there was less space for me. Eventually Pa built me a trundle bed, which we kept beneath the other bed during the day. I dragged it out each night and put myself to sleep beneath a drafty window, cold and lonely.

Gone were the days when I could look my mother in the eye without feeling my stomach cramp; wondering what she’d think of the conversations and activities that went on at the tavern. It became easier to keep to myself or stay at Pa’s side. I envied, even resented, the closeness she enjoyed with my younger siblings. Reading aloud to my family, once a real pleasure, had lost its fervor, though I continued to make the effort for the sake of children who were still learning. I also wondered what the younger boys might think someday when they too would discover the hidden world of vice awaiting them out there . . . and worried lest my sister ever be sullied by it.

And though I continued to see the mysterious specter on occasion, I was quite used to it by now, the fear long gone. If it wanted to harm us, it would have done so long ago. What’s more, it was always so deep within the forest, so far away, that I could even convince myself at times that I’d never seen anything at all. Then one life-changing night it passed by the window above my bed.

Page 2 of 3

I really enjoyed this! It reminded me of Little House on the Prairie, but with some mystery, surprise, and a good end!

Fantastic story. I really enjoyed it. Thanks!